If you’re concerned about PRs and muscle gain, it might not make sense to hear that digestive health should be a priority. Maybe you’re young, or you never experience indigestion, or you’re already pretty damn strong.

But focusing on your digestion can be key to a wide range of benefits that can improve performance, like better nutrient absorption, better immunity, and maybe better mental health. That’s why many of the more cutting edge supplements and nutrition products on the market, like the complete meal replacement from nutrition company Ample, are focusing on delivering several kinds of probiotic bacteria and fiber, as well as reducing inflammation.

So why is this really something worth thinking about? In this article we’re going to tell you six ways to improve your digestive health and why they deserve attention.

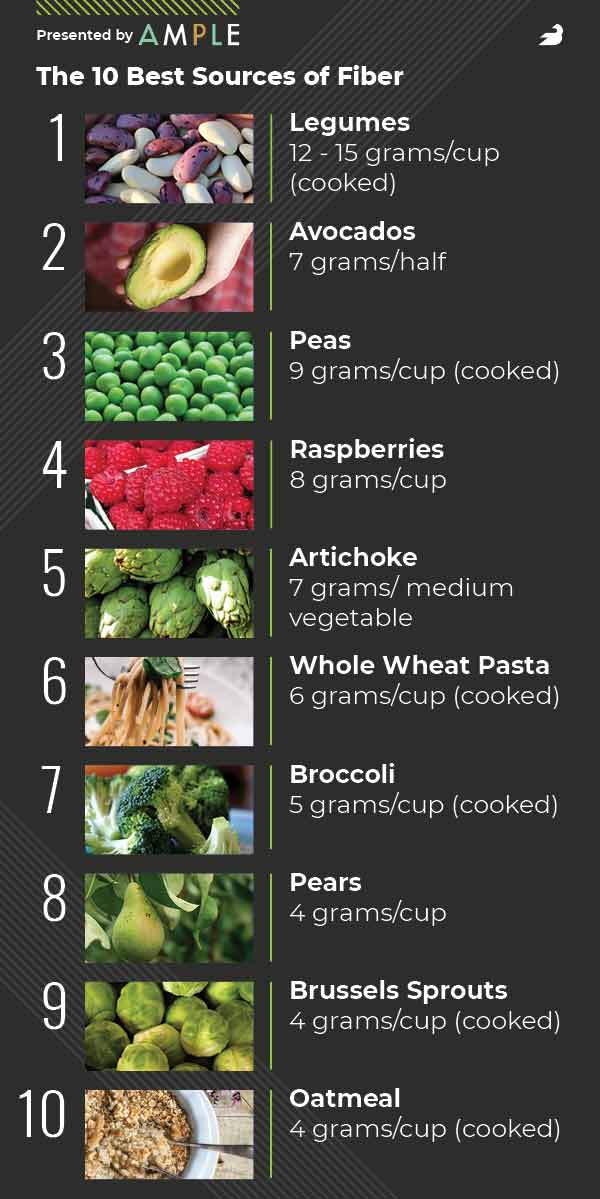

1. Eat Different Types of Fiber

The recommended daily intake of fiber is about 25 grams for women and 35 grams for men, and some experts estimate that as much as 95 percent of the population don’t get enough.(1) But besides helping to sate your appetite consuming enough fiber has been linked to lower risks for cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, gastrointestinal disorders and obesity.(1)(2)(3)

It’s extra relevant for athletes that fiber may help boost your immunity, reduce inflammation, and improve your insulin sensitivity, which means you’re less likely to store excess glucose as fat.(4)(5)

It’s important to get sources of both soluble and insoluble fiber. Soluble fiber turns into a gel-like substance in the intestines, slowing the digestion rate and helping nutrients to better absorb.(6) Insoluble fiber helps add bulk to food as it passes through your digestive tract, making for better bowel movements. Most foods have a mix of the two, though soluble fiber is especially high in beans and cruciferous vegetables while insoluble fiber is a little more common in grains.

It’s also worth remembering resistant starch, which is similar to fiber and may have benefits for your gut bacteria.(7) Ample is a solid source of soluble fiber, insoluble fiber, and resistant starch, plus it has inulin, a soluble prebiotic fiber that acts as food for your gut bacteria.

2. Eat Probiotic Bacteria

Why should you be feeding bacteria in your gut? This is a conversation about your microbiome, the environment of microorganisms that live in and on your body. In the gut, there are some 500 to 1,000 species of bacteria and keeping them healthy and thriving is linked to an enormous variety of benefits.

We discuss them at length in this article on probiotics and athletes, but in short: research has suggested that keeping your gut bugs in top shape could improve immunity, reduce inflammation, help insulin sensitivity, maximize nutrient absorption, and improve athletic recovery.(8)(9)(10)(11)(12)(13). There’s even some evidence that a healthy microbiome makes you less susceptible to anxiety.(14)(15)

All of these, of course, are fundamentally important for athletes.

All the tips on this list also contribute to a healthy gut microbiome, but it’s also a good idea to consume source of probiotic bacteria: yogurt and sauerkraut are great options. But remember that you don’t just want more probiotics, you want more kinds of probiotics. The more diverse your population is the better, which is why Ample includes 4 billion CFUs of them from six different strains, which is more than you see in your standard bottle of kombucha.

3. Consider Digestive Enzymes

We won’t say they’re essential, but there’s some evidence that supplementing with enzymes can help to prevent indigestion and enhance nutrient absorption. For example, in a 2008 study published in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, men who consumed whey with proteases, the enzymes that help digest protein, had an increased absorption rate, as measured by the amino acids in their blood and urine.(16) Other research has found that protease supplementation might help to facilitate muscle healing post workout.(17)

It seems that the body produces fewer digestive enzymes as we age and some people like to add them to their meals, particularly if they’re large, anabolic, thousand-calorie meals that you might have post-deadlifts.

You don’t necessarily need to seek enzymes in supplements, though. Tropical fruits like pineapples and papaya are known for containing proteases, mangoes and bananas have amylases and glucosidases (which break down carbs) and avocados are a source of lipase (which digests fat).(18)(19)(20)(21)(22). Fermented foods are also good bets.

4. Sleep Better

There’s really no end to the benefits of getting enough deep sleep. These days, it’s been linked to everything from higher testosterone to better immunity.(23)(24)

It can also help with digestion. When we’re sleep deprived, the body produces more of the appetite stimulating hormone ghrelin, and studies have found tired people have lower willpower and are more likely to overeat on junk.(25)(26) That’s not useful for athletes or for your digestion. In addition, sleep deprived people release more cortisol, a hormone that some research has shown can contribute to indigestion.(27)(28)

If sleep eludes you because of bad digestion, there’s evidence to suggest that sleeping on your left side is ideal as it creates better alignment for your digestive tract and helps the stomach and gastric juices remain lower than the esophagus, possibly helping to reduce heartburn.(29)

5. Manage Your Stress

Stress also has a strong link with indigestion. The idea that it can cause stomach ulcers isn’t as widely accepted as it once was, but it does increase your cortisol, which again, can produce indigestion. Stress is seen as a threat to homeostasis, which makes the body less likely to properly digest.(30)

In fact, there’s evidence to suggest that the more relaxed you are, the better you absorb nutrients. Several studies found that when your body is in a more parasympathetic state — that’s the opposite of a sympathetic state, sometimes called “fight or flight” — the body does a significantly better job of absorbing nutrients, secreting insulin, and burning calories. (31)(32)(33)(34)(35) Learning to meditate can be a great way to switch to parasympathetic, by the way.

The gut-brain connection is also why, as previously mentioned, having a healthier gut may help to make you less susceptible to stress. So taking care of both sides of the equation is a smart move.

Wrapping Up

As you can see, improving your digestive health doesn’t just mean you’re more “regular.” It can have serious implications for inflammation, immunity, recovery, nutrient absorption, sleep, and stress. If you want everything dialed in, consider products with an emphasis on different types of fiber and probiotics like Ample and make sure you manage your stress and sleep.

References

1. Mobley AR, et al. Identifying practical solutions to meet America’s fiber needs: proceedings from the Food & Fiber Summit. Nutrients. 2014 Jul 8;6(7):2540-51.

2. Kunzmann AT, et al. Dietary fiber intake and risk of colorectal cancer and incident and recurrent adenoma in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 Oct;102(4):881-90.

3. McRae MP. Dietary Fiber Is Beneficial for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: An Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses. J Chiropr Med. 2017 Dec;16(4):289-299.

4. Anderson JW, et al. Health benefits of dietary fiber. Nutr Rev. 2009 Apr;67(4):188-205.

5. Ma Y, et al. Association between dietary fiber and serum C-reactive protein. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006 Apr;83(4):760-6.

6. Wanders AJ, et al. Effects of dietary fibre on subjective appetite, energy intake and body weight: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2011 Sep;12(9):724-39.

7. Higgins JA. Resistant starch and energy balance: impact on weight loss and maintenance. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2014;54(9):1158-66.

8. Le Chatelier, E. et al. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature. 2013 Aug 29;500(7464):541-6.

9. Carvalho, B.M. et al. Influence of gut microbiota on subclinical inflammation and insulin resistance. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:986734.

10. Plaza-Diaz, J. et al. Evidence of the Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Probiotics and Synbiotics in Intestinal Chronic Diseases. Nutrients. 2017 Jun; 9(6): 555.

11. Nichols, A.W. Probiotics and athletic performance: a systematic review. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2007 Jul;6(4):269-73.

12. Bäckhed, F. et al. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Nov 2;101(44):15718-23.

13. Regulation of abdominal adiposity by probiotics (Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055) in adults with obese tendencies in a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010 Jun;64(6):636-43.

14. Messaoudi, M. et al. Assessment of psychotropic-like properties of a probiotic formulation (Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175) in rats and human subjects. Br J Nutr. 2011 Mar;105(5):755-64.

15. Schmidt, K. et al. Prebiotic intake reduces the waking cortisol response and alters emotional bias in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2015 May;232(10):1793-801.

16. Oben J, et al. An open label study to determine the effects of an oral proteolytic enzyme system on whey protein concentrate metabolism in healthy males. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2008 Jul 24;5:10.

17. Miller PC, et al. The effects of protease supplementation on skeletal muscle function and DOMS following downhill running. J Sports Sci. 2004 Apr;22(4):365-72.

18. Pavan R, et al. Properties and therapeutic application of bromelain: a review. Biotechnol Res Int. 2012;2012:976203.

19. Tursi JM, et al. Plant sources of acid stable lipases: potential therapy for cystic fibrosis. J Paediatr Child Health. 1994 Dec;30(6):539-43.

20. Bassinello PZ, et al. Amylolytic activity in fruits: comparison of different substrates and methods using banana as model. J Agric Food Chem. 2002 Oct 9;50(21):5781-6.

21. Peroni FH, et al. Mango starch degradation. II. The binding of alpha-amylase and beta-amylase to the starch granule. J Agric Food Chem. 2008 Aug 27;56(16):7416-21.

22. Stremnitzer C, et al. Papain Degrades Tight Junction Proteins of Human Keratinocytes In Vitro and Sensitizes C57BL/6 Mice via the Skin Independent of its Enzymatic Activity or TLR4 Activation. J Invest Dermatol. 2015 Jul;135(7):1790-1800.

23. Leproult R, et al. Effect of 1 week of sleep restriction on testosterone levels in young healthy men. JAMA. 2011 Jun 1;305(21):2173-4.

24. Wittert G. The relationship between sleep disorders and testosterone in men. Asian J Androl. 2014 Mar-Apr;16(2):262-5.

25. Leproult R, et al. Role of sleep and sleep loss in hormonal release and metabolism. Send to Endocr Dev. 2010;17:11-21.

26. Pilcher JJ, et al. Interactions between sleep habits and self-control. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015 May 11;9:284.

27. Hirotsu C, et al. Interactions between sleep, stress, and metabolism: From physiological to pathological conditions. Sleep Sci. 2015 Nov;8(3):143-52.

28. McEwen BS. Central effects of stress hormones in health and disease: Understanding the protective and damaging effects of stress and stress mediators. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008 Apr 7;583(2-3):174-85.

29. Kaltenbach T, et al. Are lifestyle measures effective in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease? An evidence-based approach. Arch Intern Med. 2006 May 8;166(9):965-71.

30. Konturek PC, et al. Stress and the gut: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, diagnostic approach and treatment options. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011 Dec;62(6):591-9.

31. Landolt K, et al. Chronic work stress and decreased vagal tone impairs decision making and reaction time in jockeys. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017 Oct;84:151-158.

32. D’Alessio DA, et al. Activation of the parasympathetic nervous system is necessary for normal meal-induced insulin secretion in rhesus macaques. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001 Mar;86(3):1253-9.

33. Mourad FH, et al. Neural regulation of intestinal nutrient absorption. Prog Neurobiol. 2011 Oct;95(2):149-62.

34. Tavakkolizadeh A. Role of vagal fibers in weight control and nutrient absorption. J Surg Res. 2012 May 1;174(1):85-7.

35. Acheson KJ. Influence of autonomic nervous system on nutrient-induced thermogenesis in humans. Nutrition. 1993 Jul-Aug;9(4):373-80.